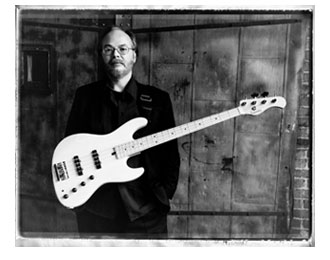

WALTER BECKER (1950 – 2017)

Obituaries for guitarist Walter Becker, who died on September 3, referred to the music he created with Donald Fagen, his partner in Steely Dan, as “jazzy,” as “sophisticated pop.” Tidy terms, perfect for limited-character exchanges (and attention spans) trafficked through social media. But, do they really cut it? Can that terse language address the impact of their efforts, the effect Steely Dan had on its dedicated followers?

When news of Becker’s death spread, it unleashed a torrent of running commentaries – remembrances, thanks, acknowledgements, appreciations, all in the service of lives changed. Many were from baby boomers whose teenage years were wallpapered with sounds emanating from radio or turntables. Though many of Steely Dan’s tracks were heard as smooth pop flaunting ear worm hooks, their complexity and polish revealed remarkable depth and attention to detail. (The group’s audiophile standards were so high, the records were routinely used to test check stereo components.)

Hit singles such as “Do It Again,” ”Reelin In The Years,” “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number, “Hey Nineteen” and “Peg” – representing airwave domination throughout the ’70s – were not throwaway ditties, designed for consumption and disposal. They were painfully constructed by creators who reveled in the role of joyful subversives.

In fact, both Becker and Fagen, as youths, were heavily influenced by the surround sound of jazz radio and recordings. Fagen bowed at the feet of Sonny Rollins and the classic releases from the Blue Note label, while Becker grew up following dj’s such as Mort Vega, the legendary New York broadcaster whose programming featured heavy doses of jazz greats, big bands and stand-up comedians. Becker acknowledged that the sounds and harmonies that enveloped him as a child provided the foundational groundwork for Steely Dan. Reportedly, he was the product of a broken home who endured a difficult upbringing. One can guess that the echoes of his early years served as both balm and inspiration. Once he met Fagen at Bard College, their music merged, their partnership bloomed.

It wasn’t enough that Steely Dan’s songs featured people who lived on the fringe of society – fugitives, grifters, lechers – and story lines that veered left from typical ’70s radio fare – the vacuity of California excess, the subterranean allure of the jazz life. Becker and Fagen were reflecting the needs of those who felt disenfranchised, with that period’s music and, possibly, life itself in post-Vietnam America. Their fans may have been like them: literary types, exceedingly smart, knowledgeable about music history and sonic fidelity, boasting a taste for the absurd, welcoming sounds that enabled acceptance of life’s weirdness.

Becker and Fagen were songwriters with a vision, bleak and funny, featuring complicated characters in situations that often tested morality and survival. The desperado lamming it on “Don’t Take Me Alive” could not have sprung from the minds of others, say, Burt Bacharach and Hal David.

I’m a bookkeeper’s son

I don’t want to shoot no one

Well I crossed my old man back in Oregon

Don’t take me alive…

Becker and Fagen were skilled at creating musical short stories rich in humanity. That they did so with precisely-produced records utilizing musicians of a very high order attests to their perfectionism. The role call of jazz players who graced their efforts is formidable – Wayne Shorter, Phil Woods, Jerome Richardson, Larry Carlton, Steve Gadd, Warne Marsh, Ernie Watts, Pete Christlieb, Randy Brecker, et al. They were subjected to exhausting challenges aimed at exceeding Steely Dan’s beyond-pop standards. (Brecker confided that at the beginning of a recording session he never gave them the good stuff. He learned to save his best trumpet solos for takes 30 and above, knowing he needed to preserve what he had while Walter and Donald pursued “perfection.”)

The game-changer for many was the 1977 album, Aja. It struck me as a perfect record – the fulfillment of bold ideas, integrating complex musics with inquisitive narratives with mainstream accessibility. “Sophisticated,” if you prefer.

As a 20-something working in rock radio, the album was offered to me precisely because it was “jazzy,” and it bumped up against the contours of the station’s programming. Its effect was immediate – a visceral zap, followed by a reckoning of the players. The title track featured a tenor solo from Wayne that sent me on a mission. Who is Wayne Shorter? Where can I find his records?

Time travel ensued, which proved the ride of a lifetime – from Wayne to Joe Zawinul, to Cannonball Adderly, accelerating through the constellations of Bird and Lester Young and Louis Armstrong, shifting into higher gears with Monk, Miles, Bill Evans, Trane and Ornette. Backwards and forwards, my side trips provided the purest of exhilarations, knowing that the genetic code for Aja is written in the bones of all these spirits. A forensic journey, fueled by the fumes of pressed vinyl.

All of a sudden, a track from Pretzel Logic, a record from three years earlier, made sense: “East St. Louis Toodle-oo,” written by Duke Ellington and trumpeter Bubber Riley, now masterfully updated to feature Becker’s wah-wah replication of Riley’s depression-era mute. Not the most obvious song choice for a rock group breaking through to teenagers in 1974. But the impulse was undeniable: that music was in their bones, without concern for the categorical differences or demands associated with genres.

I felt then (and I feel now) they were having a private laugh the whole time, opening that door, suggesting I walk through, knowing I’d be gobsmacked by my discoveries. That gesture might have been the most generous gift they offered me. Curiosity begat a calling. A career was born.

I’ve often thought about the entirety of Steely Dan, even pondering the absurdity of the band’s name, especially now that Becker is gone. Steely Dan was inspired by William Burroughs’s reference to a strap-on dildo in his novel, Naked Lunch – an amusing thought as you weigh the staying power of their music. Once Becker and Fagen found their song ideas – often wry, without precedent – they draped them in majestic hipness, showcasing a musical range well beyond other purveyors in pop music. So much of what Walter and Donald created was big. Theirs was a partnership for the ages. Any major dude will tell you.

—by Jeff Levenson